Failed, Not a Failure

Failure is an inevitable part of life. But it doesn’t have to be feared.

Author’s Note: This is part one of a two-part series on failure. You can read part two here.

At the end of 2017, I found myself unemployed.

In early December, I made the difficult decision to resign from my job as a product manager at a medical diagnostics company. The role was a poor fit for my skill set and caused me a great deal of stress that I was unable to overcome. Although there had been flashing warning signs for months that the role was going to be difficult, I chose instead to put my head in the sand.

My time at the company had started off well. I joined as a contractor that February and enjoyed the work, which involved performing various research projects to support the marketing strategy for the company’s FDA-approved diagnostic blood test. I made several friends at the company and was colleagues with one of my best friends from business school. It was a manageable workload.

Six months later, after assessing my skills and concluding that I was a good fit for the marketing team, I was offered a full-time role as a product manager. I was excited to jump at the opportunity. Now I could earn vacation and receive benefits.

On paper, being a product manager sounded doable. In reality, I was doomed from the outset. Because the office was based in Massachusetts, and I lived several hours away in Connecticut, I was able to convince the company to allow me to work remotely. They were aware of my mobility situation and understood the need to work from home, even though they would have preferred that I be on-site.

At first, I enjoyed the fast-paced environment and the feeling that I was doing meaningful work. But week after week, month after month, I gradually wore down. The accumulated stress from coordinating dozens of meetings with internal and external stakeholders, answering angry emails from hospital IT staff asking why an installation project was behind schedule, and the internal pushback I received on numerous product recommendations pushed me to my breaking point. Had I been on-site, I might have been able to iron out any miscommunications or disagreements in person, but from afar, over email (this was before the normalization of videoconferencing), it wasn’t possible. There were just too many flashpoints.

The end of the line

After four months, I couldn’t take it anymore. Despite regular check-ins with my boss, I felt isolated from the team and the rest of the company. I barely slept. When I did fall asleep, I dreamt about the job. I would wake up every day with a tension headache in the back of my neck. Any thought of work elicited negative emotions and palpable dread.

On a Saturday morning in early December, I woke up with one of these excruciating headaches. All I could think about was my endless to-do list waiting for me on Monday. I realized that my weekends were now just 48 hours of dwelling on the upcoming work week.

The night before, while looking in the mirror, I noticed more and more of my hair starting to turn gray around my temples. The job was aging me.

And for what? Status? A conversation starter at cocktail parties I didn’t attend?

I realized enough was enough. Although I loathed the thought of quitting, I knew I had to resign. It was the only way to regain a sense of balance in my life and preserve my health. I called my boss and when he didn’t pick up, left a voicemail. A few minutes later he called back, pleading with me to stay, but I was firm in my decision. It wasn’t his fault, I said, it just didn’t work out.

Although I was relieved to remove this stressor from my life, I was soon overcome by self-doubt. It was clear; I had failed spectacularly. How else could I explain being jobless two years after business school? I was supposed to be gainfully employed at this point, well on my way to a management role. I had given up two years of my life to go back to school to improve my future job prospects. I had student loans to pay. I wasn’t supposed to be back at square one, especially since I hadn’t been laid off.

In the days after the decision, I felt a sense of embarrassment and shame. Because I had failed, I felt that I needed to answer for my decisions. I obsessed over the chain of events that led me to this point. I became a nesting egg of recrimination, interrogating myself over and over again with questions that penetrated deeper and deeper into my soul until I was forced to account for the very fabric of my purpose and character.

How could I have put myself in this situation?

Why didn’t I try harder to make it work out?

Why didn’t I just stay a contractor?

Why didn’t I try harder to secure a job before graduation so I wouldn’t be in this situation to begin with?

Why did I even go to business school?

And the real doozy:

What the hell am I doing with my life?

This wasn’t the first time I beat myself up after a failure. Every other time that I had failed in life, I followed the same destructive routine, whether it was the time when I didn’t get into my dream school, or when I failed my first driver’s test. (The “No Turn on Red” sign, I learned, wasn’t a suggestion.)

But this was another magnitude of disappointment altogether. There was so much more at stake now that my disease symptoms were worsening. I couldn’t afford to be unemployed for too long. That enhanced the feeling of shame.

I couldn’t help but feel like I was a failure in life.

It was a sobering, dramatic thought, one I shot down quickly. It was easy to identify as a failure in the heat of the moment. Deep down I knew that although I wasn’t a permanent failure, I was getting way too used to failing. Worse, I didn’t know how to deal with failure in a healthy way.

After much reflection, I realized the only way that I would be a true failure was if I allowed this setback to infect my life, make me jaded, and keep me from taking future risks. If I let it become a self-fulfilling prophecy, then it would become my identity. As long as I didn’t let that happen, I would ultimately be okay, no matter how much it hurt in the present.

To emerge from this darkness, I would need to upend my relationship with failure. This would require a change of mindset. But how?

We aren’t taught how to handle failure

After I quit my job, I went on a quest to better understand how to handle failure. (I had a lot of time on my hands.) I knew failure would always be painful, but I wanted my response to blunt that pain. It would require trial and error and reading stories of how others dealt with similar setbacks.

I don’t know about you, but I was never taught resilience strategies in school. I don’t recall ever learning a framework for dealing with adversity or handling failure. (If I did, it didn’t stick!) For whatever reason, it’s just not something that’s widely taught. Most of what I have learned about failure has come through life experience. A few resilience strategies taught in high school could have gone a long way. We are taught every other conceivable subject, except how to overcome failure. And yet, what could be a more important topic to learn at a vulnerable age?

Without a formal framework, the real world becomes our teacher, and the real world is unforgiving. We are hit with constant failures in life — schools that rejected us, jobs we didn’t get, bankruptcy, divorce, etc. (Meanwhile that friend we grew up with just got promoted, again.) We start to believe that life is a zero-sum game, where the more failure we face, the less likely we are to ever achieve our goals. Yet, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

There’s a reason that we remember failure more than success: failure is excruciating. The negatives tend to outweigh the positives, no matter how much we know they shouldn’t.

If you’ve ever gambled, it is the losses you remember, not the wins. If you own a business, it is the one negative review that stays with you instead of the 99 positive ones. For writers, it’s the negative comment from a mindless troll that you focus on instead of the positive feedback.

Failure hurts, yet we are often unprepared to seek the remedy. We are willing to do the work, we just need some guidance to show us the way.

“You may encounter many defeats, but you must not be defeated. In fact, it may be necessary to encounter the defeats, so you can know who you are, what you can rise from, how you can still come out of it.” ― Maya Angelou

No epiphanies. No guarantees. Just a process.

The goal of today’s newsletter — the first in a two-part series — is to get comfortable with failure and learn how to accept it. My next newsletter will dig into the nuts and bolts of how to turn a failure into a future success, which becomes easier once we understand how to process failure and put it in its proper context.

What follows is what I have learned from my many failures in life. Some of these lessons were learned immediately after quitting my job, others much later. These lessons have served me well over the years. They are presented in no particular order but are each independently useful ways to frame failure.

The lessons still come in handy, because I still fail quite frequently. And it’s still miserable! But at least now I know what to do when failure strikes. After all, it isn’t about avoiding the pain, but minimizing the impact. We can’t live a failure-free existence, even if we took the safest, most risk-averse path imaginable. Besides, what kind of life would that be? Failing is a feature, not a bug, of life, even if it hurts in the short term.

Putting failure in the right context

Failing is not the same as being a failure, but it’s hard to tell the difference. Being a failure conveys a sense of finality. It says that because you failed this time, you will always fail, and there is nothing you can do about it. It is the realm of fatalistic thinking, of surrendering agency. In times of great adversity, failure can wound our psyche, causing us to believe that future failure is pre-ordained.

But what is failure, really? It is merely something not working out the way we had hoped. Being denied something we wanted. Not achieving success. Not getting our way. Not winning the game. Not being the person we thought we would be at this stage of our lives.

But failure is precisely what makes us human. We aren’t perfect, and we aren’t supposed to be. Humans have been dealing with failure ever since there have been humans. Failure is baked into the human condition. Understanding failure is the first step toward seeing it more clearly. When we see it for what it is — a fact of life — it begins to lose its paralyzing grip on our lives.

“You build on failure. You use it as a stepping stone. Close the door on the past. You don't try to forget the mistakes, but you don't dwell on it. You don't let it have any of your energy, or any of your time, or any of your space.” - Johnny Cash

We’ve been through this before

Many of my struggles with failure occurred because I would let the setback snowball out of control instead of addressing it head-on. It punched me but I didn’t punch back.

The low points were so low because I would conveniently forget that I had faced hardship before. It was as if all that I had been through with my disease — declining mobility, finding acceptance, overcoming my panic attacks, purchasing adaptive equipment — didn’t matter. I had done hard things before and deserved to recall my achievements. When I quit my job in 2017, I should have thought back to the previous time I was unemployed after the 2008 financial crisis. It worked out then; there’s no reason it couldn’t work out now.

When you encounter a failure, before you do anything else, remind yourself: I’ve been through this before, and I can deal with it again.

“Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

- Winston Churchill

We all fail, we just don’t know it

Here is another helpful reminder: everyone encounters failure.

Unfortunately, we tend to believe that everyone else lives flawless, perfect lives. This is because we as a society shy away from sharing our low moments. We don’t want to expose our setbacks and failures, so we paper over them.

As a consequence, what we see on social media are the best versions of everyone else:

Someone shares on LinkedIn that they got their dream job, but they don’t tell you about the other 48 dream jobs they didn’t get.

You hear about the school someone got into, but not the schools that rejected them.

Your coworker gushes about being in love, but they don’t tell you about the years of bad dates that preceded finding “the one”.

To be clear, we shouldn’t root against someone’s good fortune. However, only hearing about successes creates a distorted feedback loop that makes us feel like we’re the only ones who have ever failed.

Failure is a form of vulnerability, and many of us are not comfortable sharing our vulnerabilities, because we think that people will judge us. That is fair. But in hiding our collective failures, we are unable to find solace in others who understand what we’re going through. For example, when I told my friends about my job situation, I learned that several of them had been unemployed in their careers and had felt the same fear and self-doubt. That was reassuring.

"Someone else's success is not your failure." - Jim Parsons

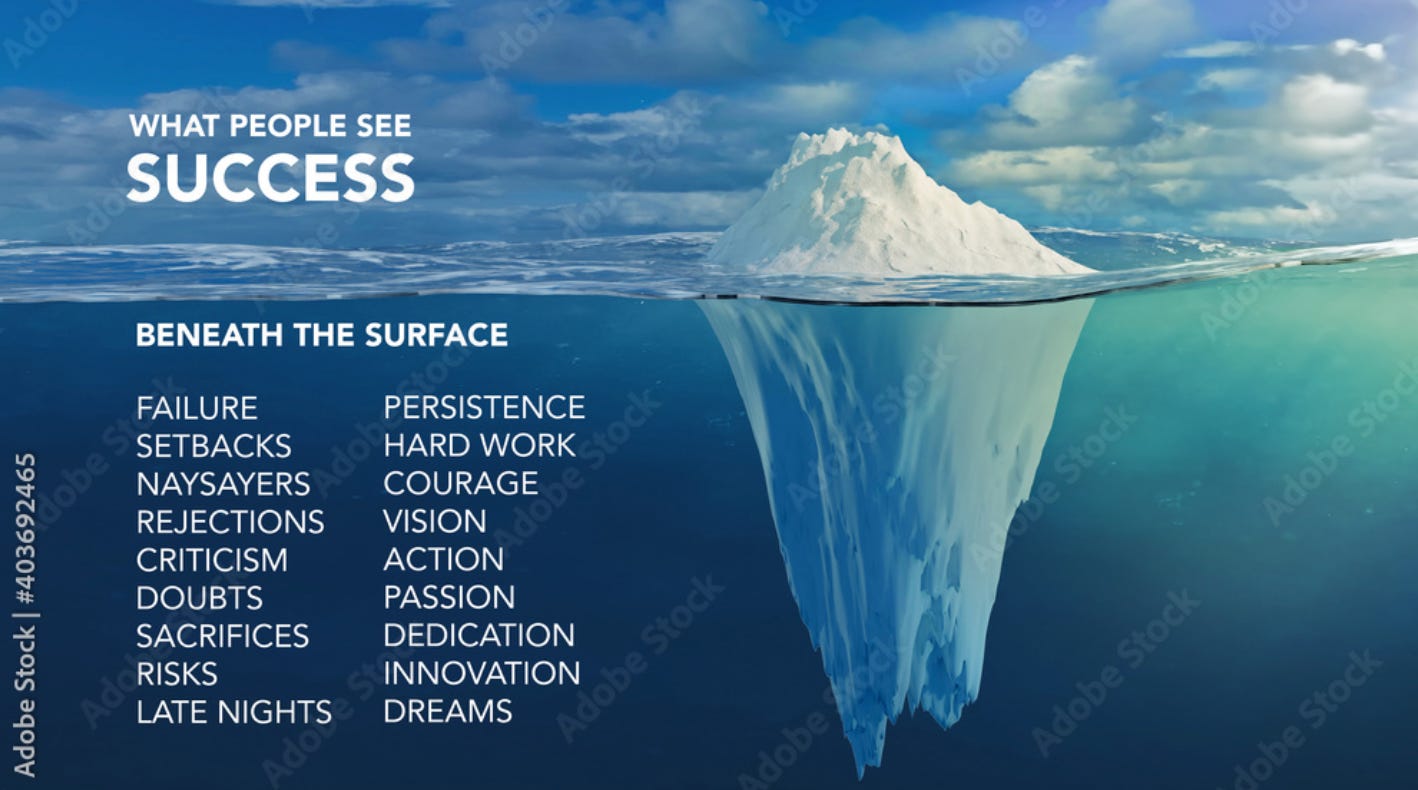

Failure is the other 90% of the iceberg

To further illustrate this point, there is a helpful drawing of an iceberg that you may have seen on social media, such as this one:

The gist of the image is that we only see the 10% of the iceberg above the surface. This is outward success.

Yet, below the surface is the other 90% of the iceberg that provides a fuller picture of its true shape. For every 10% above the surface, there is a less glamorous 90% hidden out of sight. Visible success is always accompanied by invisible failure, self-doubt, worry, persistence, and other difficulties. When we hear about someone’s success, we conveniently don’t hear about the other 90%. We see the same pattern even when we think about our own achievements. What were our successes born out of? You guessed it: prior failures.

Failure doesn’t mean you did anything wrong

Failure attacks our pride. We think it’s an indictment of our character, when in reality, more often than not, we didn’t do anything wrong. Sometimes we mess up. But not always. You can do everything right and still have a bad result. Think of a lost game or a failed experiment. You can follow your process, do the work, put in the effort and it doesn’t work out. It happens.

Statistics are not on our side. We won’t get every job. We won’t get into every school. Sometimes we have to make decisions with incomplete information and hope for the best. If it works out, great, but if it doesn’t, that’s not an indictment against us.

This won’t always make failure easier to overcome. But it can help us start to disassociate failing from becoming a failure. I’ve had many jobs in my career; I was bound to fail at one of them.

"There is a very fine line between success and failure. Just one ingredient can make the difference." - Andrew Lloyd Webber

It is okay to vent

That said, knowing we are going to fail at some point doesn’t make it easier when it finally happens. Even knowing failure can help us long-term doesn’t make it easier at that moment when adversity strikes.

Perhaps the best piece of advice I’ve gotten on failure came from my career counselor at Boston College. When I didn’t get a full-time job offer after my summer internship in business school, I was livid. I was mad at the world. I sulked. And that was just in the first ten minutes.

That afternoon, I scheduled a meeting with my counselor. She could sense my frustration when I showed up at her office. I thought I had performed well on the internship and didn’t know why I didn’t get the offer. Toward the end of the meeting, I became defiant and said that I would double down on my efforts and find a better job.

She stopped me mid-sentence and offered a great piece of advice:

“Chris, take the day. Be pissed. Tomorrow, start fresh.”

It was simple advice but it underscored an important point: it’s okay to vent for a little bit; we just can’t let our anger and frustration fester. It’s important to process our negative emotions, up to a point. This advice has served me well even beyond the context of failure, whether it’s having a bad day, a fall, pain, etc. Today stinks, tomorrow will be better.

There are situations when you won’t need a full day to vent. If it’s something small, like a failed experiment, or a missed shot, it’s easy to shrug it off and continue. But if a setback has you feeling sad, realize that it’s a normal emotion. You don’t have to brush it off and minimize it. However, if three weeks go by and you are still in the exact same funk, that might be a sign that you need to talk to someone.

“Everything on earth has its own time and its own season.”

― Ecclesiastes 3:1

“No” might just mean “not yet”

When we develop a healthier relationship with failure, we start to see that it isn’t the end of the world.

Not all failures mean that the window of opportunity has closed for good. Two moments in my life illustrate this well.

The first moment actually began way back in 2004. I may have gone to Boston College for my MBA, but it was the second time I applied to the school. In 2004, it was my dream school for undergrad. Unfortunately, I didn’t get in.

I was crushed and swore off ever stepping foot on that campus again, a ban that lasted five years. Then in 2009, I moved to the neighborhood. One morning, I decided to go for a walk and check out the campus that could have been my home. The emotions came flooding back, and it opened my eyes to the possibility that maybe I could still attend the university, just in a different capacity. In 2014, I applied to their MBA program and got in.

I wouldn’t trade my undergraduate experience at Northeastern for anything. I made lifelong best friends and got to live right in the middle of the greatest city in the world. To experience both schools, at different times in my life, ended up being far more satisfying. The right time for me to attend BC wasn’t 2004; it was 2014.

The second moment was after quitting the product manager job in 2017. I thought it was the ideal role for me at the time, only to find out that I was so very wrong. In the aftermath of that failure I regrouped, and through a series of fortuitous events, was connected to a woman who would become my boss at the Muscular Dystrophy Association. Five years later, I can see that I made the right decision to quit; something better was waiting for me all along. Had I not quit, I wouldn’t have been free to attend the conference where I met my future boss. It’s funny how life works out sometimes.

Age is just a number. Just because we didn’t achieve something at a certain time doesn’t mean we never will. Just because we failed once doesn’t mean we will always fail.

Failure is hard when it happens, but with a little distance and perspective, you can see that things usually work out, or the failure wasn’t as bad as you had expected.

Turning around failure

In two weeks, we will explore how to capitalize on our failures. For now, know that failure can be a very good thing. It can teach us valuable lessons and provide us with data that we didn’t have before, data that will allow us to make a different decision next time.

Ultimately, failures can change our lives for the better. They are a healthy part of growth and an excellent learning opportunity.

Now comes the fun part!

Click here for part two of this essay.

“When we give ourselves permission to fail, we, at the same time, give ourselves permission to excel.” - Eloise Ristad